by Colin Ferster

OpenStreetMap (OSM) is the volunteered map of the world. Contributions are wide and diverse, from hobbyists to commercial interests. OSM spans across boundaries and allows many uses. That makes it a compelling dataset for personal, research, and commercial use!

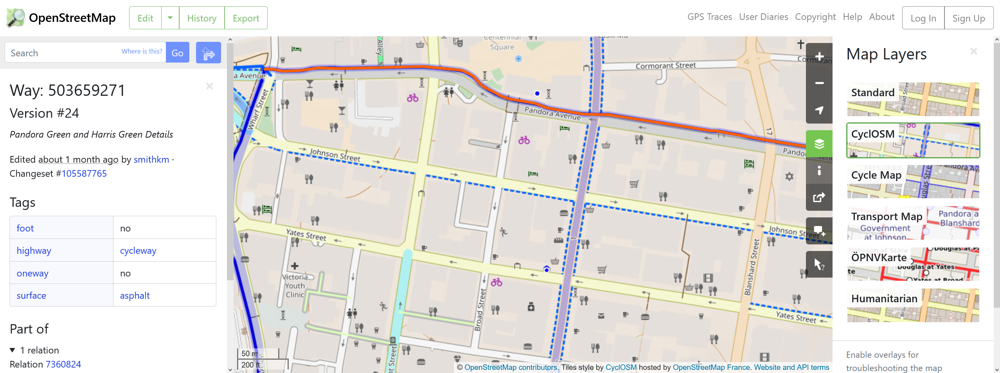

As part of the Canadian Bikeway Comfort and Safety Classification System (Can-BICS) project, we are using OSM to map bike facilities across Canada.

Can-BICS is a system of classification for bike facilities that aligns engineering guides, open data provided by cities, and current bicycling safety and preference research into a common classification framework. We are developing queries and GIS operations to classify OSM across Canada according to Can-BICS labels.

As part of developing this classification, we collected more than 2000 ground reference points to train the classification and evaluate accuracy. We are also becoming active editors of OSM cycling data (in the spirit of leaving the campsite nicer than we found it). In the process of viewing the data, we are amazed by the extent and detail of mapping (if you contributed, thank you!!).

We put together some tips for people who want to edit bike data. For experienced editors, we have four recommendations for improving OSM bicycling data in Canada from the perspective of active transportation researchers.

Getting started

For those starting out, the best place is learnOSM. It introduces OSM, navigation, and basic editing and is well worth the time.

For mapping bicycling features, the OSM wiki has two key reference pages, and many more specific pages to explore:

Bike Ottawa has an excellent guide for consistently tagging bicycling features. OSM Can-BICS aligns with this coding scheme, and I use this reference in my own editing. The only limitation is for local street bikeways (which may be uncommon in Ottawa). See the recommendations section below for more about local street bikeways.

My experience

For contributing to bicycling data for safety research, I find myself adding tags to paths and bikeways on roads. I use OSMAnd for navigation on my smartphone (or just look at OSM in a webrowser when I'm planning a trip), and if it doesn’t match what I see on the ground, I will try to make it better! My favourite approach is to pick up a free tourist map and mark it up with a pencil while I’m riding my bike or visiting a place. There are tidier approaches, like field papers . I also refer to aerial and street level imagery from Bing Streetside or Mapillary(both have sharing agreements with OSM). Finally, I often spend some time rectifying pdf or paper maps from municipalities against OSM to find missing features.

Recommendations for improving the quality of cycling data for active transportation research

- Add surface tags to paths and trails. Surface is important for accessibility (Kay Teschke said “so many people need smooth surfaces beyond cyclists”). Yet 20% of our sample of multi-use trails was missing surface tags. Unpaved trails are great (they provide connectivity, recreation, and more), but providing surface tags on OSM will help the people who need accessible facilities find them and the information will help active transportation researchers too.

- Map separation between pedestrians and bikes using

segregated=yesor separate geometry depending on the situation. Bike paths that are separated from pedestrians are a recent development in many places in Canada that are helpful where there are high volumes. They are associated with lower collision severity compared to multi-use paths.

- Map traffic calming on local street bikeways. One of the greatest challenges we faced in developing OSM Can-BICS is distinguishing local street bikeways (which have traffic calming and diversion), from shared lanes on major roads ( which have higher risks and severity of collisions)! Even a two lane residential road with a 50 km/h speed limit (first example below) is a much different experience than a greenway with traffic calming that forces traffic to slow down (second example below). We are having trouble on residential roads that are borderline. It’s helpful to map the features that make these good for riding: reduced speed limits, traffic calming features, and traffic diversion.

- Map both the good and the bad. One of my favourite things about OSM is that the mapping reflects the bicycling experience: great bike paths are seldom missing, while questionable shared lanes or sketchy painted lanes are sometimes missing. For bicycling safety research, it’s helpful to know where the terrible shared lanes on major roads are too. The danger is that this might attract people to ride there by giving it more visibility on the map. Make sure that the other road attributes are included for warning (e.g. # of lanes, speed limits, on-street parking etc.).

Anything to add? We would love to hear from you.